Spreads versus yields

Answer: it's the spread on yields.

Since 2023, the question of what matters more, credit spreads or credit yields, has been a surprisingly persistent one1. The volume of this question tends to rise as spreads fall and, accordingly, I was asked about this subject twice in the last month. So, if you are wondering why on earth I am writing this, blame those people.

They deserve it.

What even is a spread?

I have long said, only half-joking, that the hardest question in credit is “what is a spread”?

In corpoate bond markets, a spread is the difference between the “yield”2 on a security and some other “yield” - usually that of government bonds, in which case it could be called the G-spread (or T-spread or bund-spread), spread to benchmark, or OAS (to treasury). But it can also be measured to the swaps curve, in which case it is likely to be called the I-spread, Z-spread (to swaps), OAS (to swaps), or ASW3.

There is also the spread between two bonds, which is strictly a spread-of-spreads and is usually referenced when talking about relative value; for example, the spread between triple-B and single-A credit. And none of these should be confused with swap-spreads which are to do with interest rates4.

But in very general terms, a credit spread is the return you expect to receive in excess of some other reference rate in return for taking credit risk. As such, it’s a barometer of credit valuations - how rich the asset class is when spreads are tight, or how cheap corporate bonds are when spreads are wide. For this reason, along with a significant dollop of inertia, almost everything within credit is done with reference to spreads. If yields happen to be high (or low) that is, at its core, a comment on the value (or lack of) in the underlying government bond market.

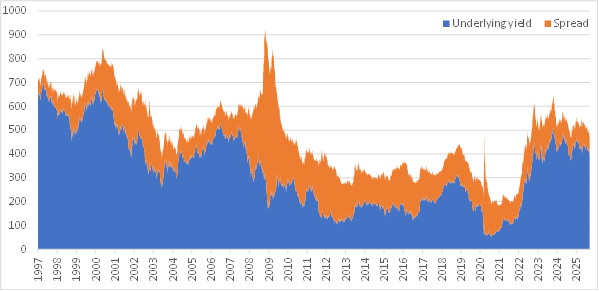

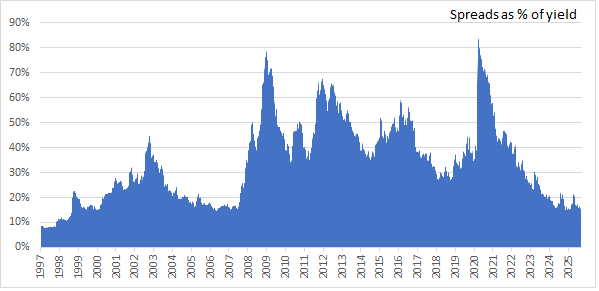

And yet, at the start of 2023, there was genuine concern that decade-high yields would be a negative for credit, as government bonds returned from their extended sojourn in ultra low (or even negative) yields. This conversation often involved a chart of spreads as a percentage of yields, arguing that the relative pick up was small enough to deter investors and asset allocators. For once being European was an advantage here - the same chart of €-IG has an extended period of divide-by-zero error that helps hammer home the point that this metric doesn’t actually correlate to anything.

When do spreads matter?

Despite worries that higher yields would cause money to flood into government bonds at the expense of corporate credit, over the last three years investment grade markets have seen strong demand on the back of steady inflows - it turns out that higher yields make credit (and fixed income in general) more attractive. As a result, $-IG spreads made 30y lows earlier this year and €-IG is hovering just above the post-GFC tights.

Surely this ends the debate: yields matter more than spreads. Demand for the asset class continues unabated. Long live the king!

Well not so fast. After all, if I have learnt anything from 15 years as a strategist it is the ability to argue both sides of the table and to make things more complex than they might initially seem.

First of all, spreads absolutely do matter when it comes to future returns. If nothing happens over its lifetime, the spread on a corporate bond very accurately represents the expected excess return for holding that bond versus the reference instrument. As long as the bond survives to maturity, it pays exactly what it says on the tin5.

And where spreads sit in their historical range also gives us some sense of the range of potential near-term returns - with spreads near their post-GFC tights, it’s unlikely that credit will generate materially higher returns than its carry6, but there is a high likelihood that spreads will be much wider at some point in the next 1-3 years. This creates a downward asymmetry in the distribution of returns for active investors, who do not just hold bonds to their final maturity.

So yes, yields are high and clearly people are happy to buy corporate bonds on that basis. But who are these people and why are they buying corporate bonds over government bonds when the marginal return is so low? Those are the real questions that we should be asking.

Who buys credit and versus what?

It would be very long, and rather dry, to discuss the broad range of investors who buy corporate bonds7, but a whistle-stop tour will help to start clarifying what is going on in credit, under the bonnet.

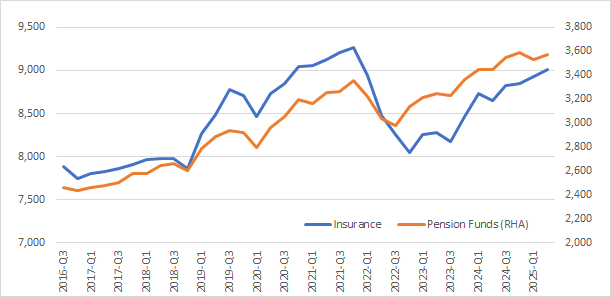

Insurance companies (investing their own money): European insurers operate under the Solvency II framework, which lays down detailed guidelines on various asset classes. For corporate bonds, the key metric is usually spread to government bonds, as the incremental capital charge is relative to Govvies8. In my past life I showed that allocations to credit by insurers have been remarkably stable over the last 10 years, despite the wild swings in both credit spreads and interest rates, reflecting their rigid regulatory framework.

Pension funds: Pension funds value their investments against pension liabilities that are discounted in various ways depending on the jurisdiction. In the UK this used to be the AA corporate yield curve, while in the Netherlands it was the Euro swap curve. However, all regions tend to have a higher demand for fixed income as yields rise (to a point), as this usually increases their accounting solvency and triggers bond buying to “de-risk” their investments.

Households: A menagerie of retail savers, from High Net Worth Individuals to moms-and-pops. These savings will generally flow into one of two basic products: either actively managed corporate bond funds, or structured savings products that are backed by portfolios of bonds. Both products are generally marketed on a combination of past performance and/or their headline yields.

Further, it is important to bear in mind that the flows into credit are not just a function of valuations but also of the total amount of assets in the system - valuations drive allocations within a portfolio, but in recent years those portfolios have, themselves started to grow at a higher rate. For example, Euro Area insurance companies have seen their total assets grow by c.€1trn since Q4 2022, and pension funds by c.€0.5trn over the same period.

With equity valuations and coupon reinvestment flow surging, there is simply more money to put to work - everywhere. So while the marginal investment to credit might be lower at tight spreads, that is being offset as the overall pie continues to grow. Indeed, the rapid surge in equity valuations has almost certainly left many investors with an overallocation to stocks - which then needs to be rotated back into fixed income, including credit.

It’s the retail bid, stupid

Given the very rough outline above, it’s pretty clear to me that the demand for credit is overwhelmingly coming from households (via savings products) - albeit with further support from pension funds (especially in the UK) and insurers9. Indeed, anyone who has been active in credit markets over the last two years will have been bludgeoned into submission on the topic of Fixed-Maturity Products - savings products that promise a fixed return on a future date and have been enormously popular in France and Italy. Estimates are hard to come by, but inflows have been in the order of €60-80bn per year over the last three years - similar in magnitude to the buying power of the ECB’s Corporate Securities Purchase Programme (CSPP).

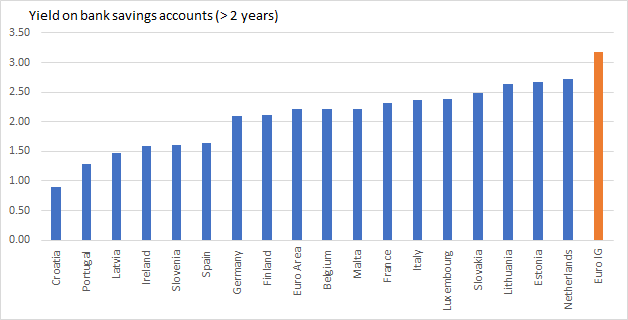

As the marginal buyer of credit, their activity is critical. So what is the outlook? On the one hand good: the spread for many of these investors is versus bank deposits, and bank term deposits currently yield a lot less than the c.3% on €-IG.

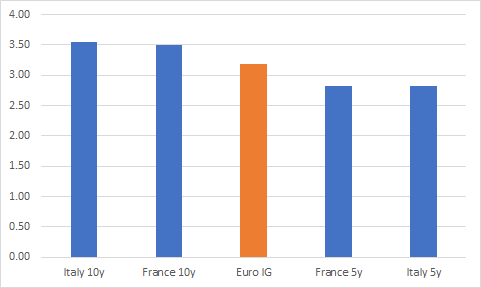

What is more tricky is the relative value of credit versus BTPs (in Italy) and OATs (in France). There have already been a few red flags raised, with €-IG now trading below the 10y OAT in yield. But, while this is a watershed moment of sorts, credit is a 5y product and the reference point should be 5y OATs where there is still daylight. Still, the point stands that the biggest retail buyers of credit have been in Italy and France, and if they could achieve the same or higher yield in EGBs, they would likely shift.

That said, there is an equal chance that the fund managers will shovel more corporate hybrids into their funds to pump up the headline yield.

I say this, but I am also aware that in 2023 I hosted a panel at a credit conference where this topic was discussed and all four panellists answered “yields”, so perhaps the question only really exists in the minds of sell-side strategists.

Yields are also a complicated idea, evidenced by feedback from one reader that they were not sure if a yield really requires the coupons to be reinvested. It does. If you need to convince yourself, consider a par-bond with a 5% coupon (which will by definition have a 5% yield). Consider the cashflows and convince yourself that they do not sum to a compounded annualised 5%.

No, I did not make these up. Go look at the YAS page on a Bloomberg terminal if you don’t believe me.

I note with a pained face that the rates market can no longer agree which way round this one goes, somewhat defeating the point of its existence as we still have to state whether bonds or swaps are outperforming.

More or less.

For those eyeing the pre-GFC tights, I would note that during that period European banks traded at exceptionally tight levels due to implicit government backstops. There was also a huge bid from structured credit in the form of CDO’s.

You will no doubt, therefore, be excited to hear that I intend to do this specifically for the long end of yield curves in the future.

It is (a lot) more complicated than this, but in essence there is higher capital charge for corporate bonds versus government bonds, and so the spread on corporate bonds has to be high enough to justify this additional cost to the insurer.

For anyone at the back shouting “Taiwanese lifers” - their demand for $-IG is driven by retail savings products that they sell domestically.

Interesting piece. Should spreads be thought of as an absolute pickup over risk free rates, or in percentage terms? Surely T+50bp is a lot more interesting when UST is 100bp versus when UST is 400bp.

Also can spreads ever be negative? Should a corporate ever have a yield lower than the risk free rates?