Source: Google Gemini

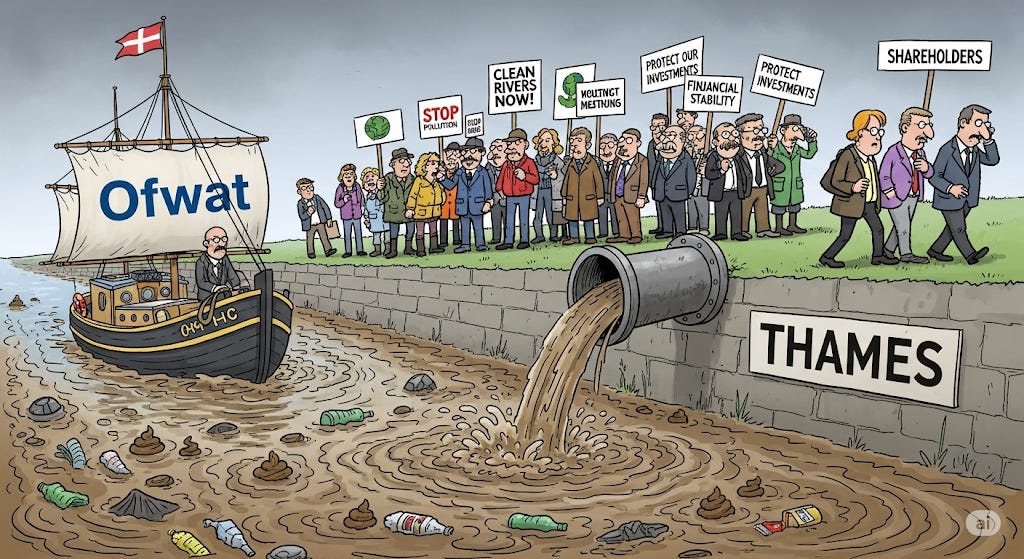

So farewell then, Ofwat. The UK government has announced that the regulator will be abolished and a “new, single, powerful” successor will be established for England. This was one of my more off-piste calls for 2025 - it’s not normal for a credit strategist to forecast the demise of a regulator, but it was part of my bullish thesis on UK water coming into the year. A reset of the regulatory framework had become a necessary step in rehabilitating the sector, and the flurry of UK water bond issuance since the government’s announcement is not a coincidence.

Why was a reset necessary? Because the regulatory framework was fundamentally broken: first by Ofwat and subsequently by the failure of Thames. By mid-2024, the sector was equally maligned by the public, investors, and ministers - the only possible outcome was a new regulatory framework, and a new regulator was, to my eye, the fastest way to wipe the slate clean. That doesn’t mean that I expect anyone to be held accountable; I imagine almost everyone at Ofwat will either be pensioned off or shuffled into the new regulator. But for investors (both credit and equity), the war is almost won: bill rises and higher investment are on the horizon.

Specificially for Thames, I expect a fudge. The remaining standoff is over “hundreds of millions” in potential fines, but if the government followed through on the threat to push Thames into SAR1 it would be on the hook for approximately £4bn. This is a bad trade for the Chancellor, so I expect creditors will stand their ground and negotiate an outcome in which Thames pays some fines but the costs are offset by bill increases.

A hitchhiker’s guide to the regulator

My first look at Thames was in late 2023. The utilities analyst asked me what I thought the UK government would do if Thames got into trouble - knowing nothing of the situation, I nodded along in agreement that government support was probable and that senior bondholders would be spared from pain. With hindsight, I'd have done well to keep my uninformed opinions to myself.

By March 2024 the utilities analyst had changed and Thames was spiralling out of control. A widely expected equity injection failed to materialise as Ofwat tightened the screws in response to increasing media outcry over sewerage releases into rivers. The shit that had been hitting rivers was now starting to hit the fan.

The new utilities analyst didn’t ask me my opinion (!) but, given the importance of the sector to sterling credit investors, I listened carefully and started to piece together the issues. I quickly came to the conclusion that Thames, and the broader water-sector, was in an impossible situation - and it was almost entirely due to Ofwat.

For the unfamiliar, the regulatory framework for UK water companies is horrendously complicated: for each company the regulator generates spreadsheets with dozens of tabs and thousands of cells. But at its core, the key concepts are simple: UK water companies operate assets for water extraction, purification, and distribution along with sewerage collection and treatment. Every 5 years, Ofwat determines a level of investment (new assets) and an allowed return on those assets: from those numbers it determines how much bills are allowed to rise. The complexity comes from how Ofwat assess the relationship between bills and profitability, modelling the entire water business including convoluted debt and capital structures.

On paper this seems like a reasonable framework. The regulator sets targets for water companies to meet in terms of service satisfaction, pollution etc., agrees a level of investment to meet these targets, and ensures that the return on investment is not excessive. But in practise Ofwat had a very poor set of political incentives - namely, Ofwat’s only real performance metrics were how much bills rose, and how many companies were caught being naughty.

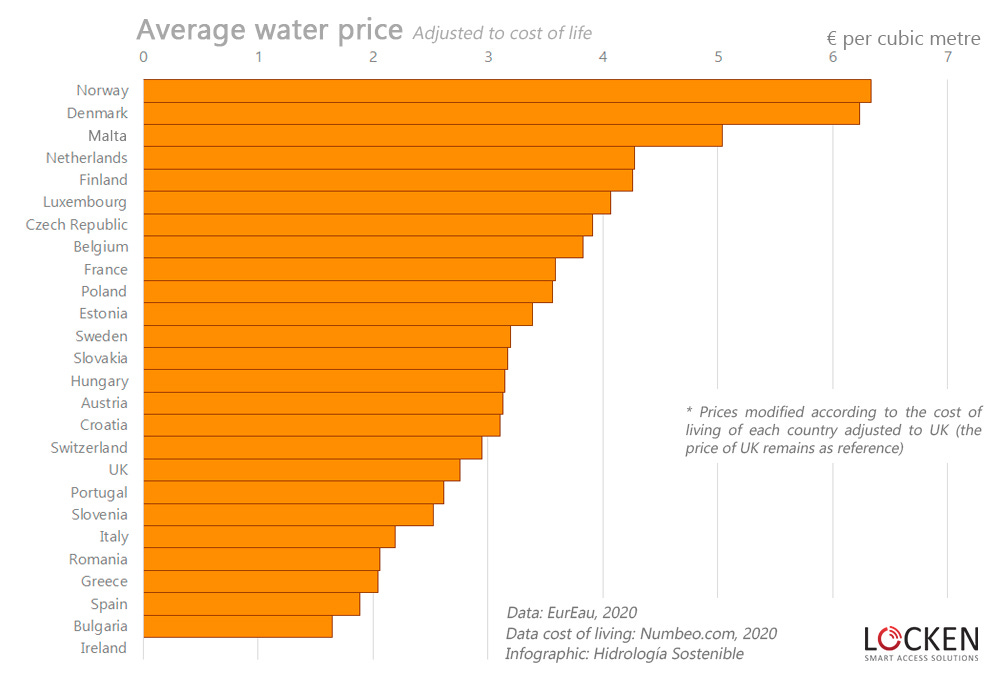

As a result, Ofwat was highly motivated to push down on bills while being relatively light on enforcement, as too many fines would bring into question how effective the regulator was at policing behaviour. And this is what happened: the cost of water in the UK remained low versus other European countries, but at the cost of chronic underinvestment and lax oversight.

https://smartwatermagazine.com/news/locken/water-ranking-europe-2020

Regulatory driven underinvestment

As Charlie Munger once said “Show me the incentive and I'll show you the outcome”. Ofwat was heavily incentivised to keep bills low, and the two levers it had to achieve this were (1) to push back against “excessive investment” by water companies and (2) to overestimate the return on equity for water companies.

The implications of (1) are pretty self-explanatory and on average Ofwat lowered the allowable Total Expenditure by 7-12% across the last six price reviews, spanning 30 years. In other words, Ofwat consistently told water companies to invest less, as a direct result of the regulator’s determination to keep bills low2.

Alongside this tendency to minimize investment, Ofwat was willing to allow very high levels of financial leverage (debt) at water companies as this pushed the returns on shareholder equity higher without raising bills. In the 30-year secular bull-market for interest rates that spanned most of the post-privatisation period, this worked. Water companies took on high levels of debt, but because interest rates were falling this was often at a lower cost than assumed by Ofwat at the start of each maintenance period. As a result, water companies made a slightly better return on equity, making the regulatory framework look sustainable while keeping bills low.

But when interest rates rose in 2022, the music stopped. The cost of debt, and there is a lot of debt, started rising and public outrage was building over waste water spillage. Ofwat was forced to recognise the massive underinvestment that had accumulated and large bill increases became inevitable. But the same public outcry that forced Ofwat to acknowledge the lack of historical investment also made it impossible to increase bills to pay for the necessary remedial work.

Source: BBC, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-berkshire-67088859

Ofwat was faced with two basic options. First it could admit that underinvestment over previous decades (and under enforcement) was a feature (not a bug) of regulation, and that the only way out of the hole that had been dug was to push up bills and start to accelerate investment. The second option was to blame shareholders and Thames.

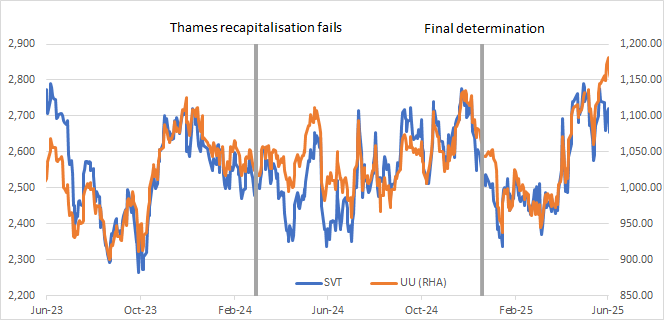

Naturally the regulator tried to single-out Thames as a uniquely bad actor. But, as the same problems started appearing across the sector, it soon became clear that the regulatory framework was rotten. In part, markets forced the hand of both Ofwat and the UK government, as contagion across share prices and credit spreads indicated investor dissatisfaction with the regulator.

Source: https://uk.investing.com/equities

Many argue that the problems in UK water are a primarily result of private equity taking excessive payouts, but the shareholders that bought Thames in 2017 never took a dividend and ultimately wrote their stakes down to zero. So if financiers are to blame, the seeds were planted in 2010 and somehow we muddled through for 15 years before noticing what was going on. Personally, I believe that it is more reasonable to say that UK water companies were raided by Ofwat to the benefit of households, who enjoyed abnormally low water bills for decades - but at the cost of future billpayers. Yet another case of intergenerational transfers?

Ratings: Mostly guaranteed

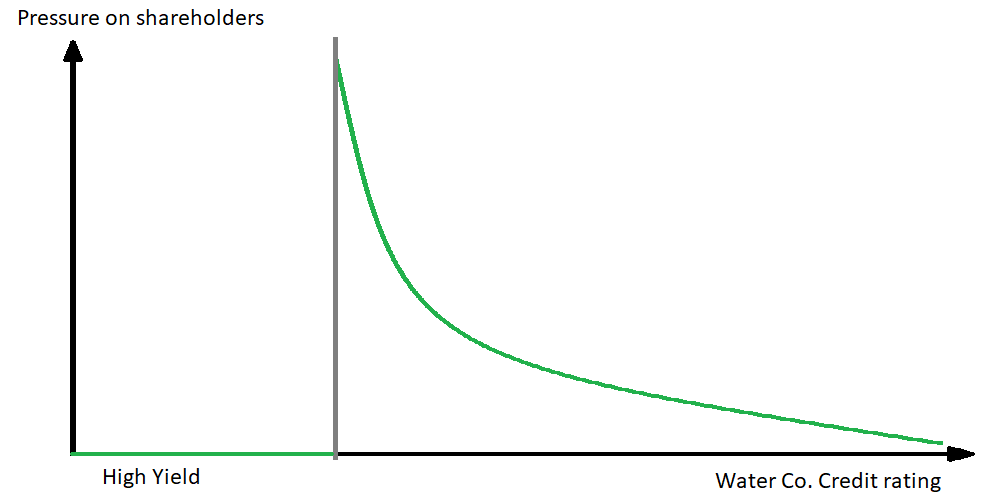

As the situation deteriorated, I talked to more and more bondholders and was surprised to hear constant reference to how the regulatory regime required Thames to remain investment grade. There was genuine anger from bondholders towards Ofwat as Thames’ bonds were steadily downgraded, perhaps more so than the company.

It was true that the regulatory framework required water companies to maintain an IG rating or they would lose their license to operate3. But this had, apparently, been interpreted as an implicit guarantee that these issuers would to remain Investment Grade no matter what. This was a fundamental misrepresentation of the regulatory framework, possibly due to a deeper misunderstanding.

A regulator cannot guarantee your bond will always be IG rated - after all the rating agencies are independent and no-one, certainly not Ofwat, could guarantee the ratings on your bonds. What the regulation did was threaten to wipe out shareholders in the event that a water company lost its IG ratings, creating a massive, asymptotic incentive for shareholders to support the company’s debt ratings. But, critically, this incentive fell away as soon as the equity was written down.

By construction, the regulatory framework would have no traction if shareholders voluntarily wrote their stakes down to zero, which is exactly what happened in April 2024. At that point Ofwat had no leverage - you can’t threaten shareholders who have already walked away.

Initially the credit rating agencies gave some leniency, in the hope of a potential white-knight rescue. But the shareholder logic was indisputable: there was zero, indeed negative, value in Thames for shareholders without higher bills, and Ofwat was unable to deliver those bills because to do so required it to admit that it was at fault. Thus, a restructuring was inevitable which would, by definition, mean Thames bonds falling to sub-investment grade ratings.

The restructuring at the end of the framework

Based on my personal understanding of Thames balance sheet, the political economy of Ofwat, and the regulatory framework, I concluded that Thames was cooked - it would be junked and most likely restructure. Admittedly, by April of 2025 this was not a groundbreaking opinion - though many legacy bondholders still hoped that the regulatory framework might somehow kick in to save the day.

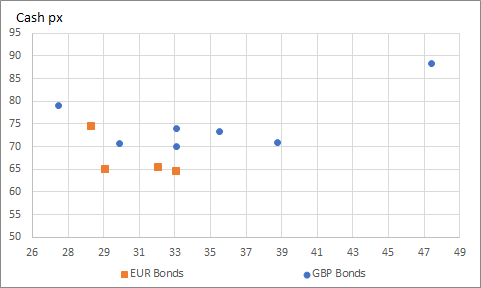

The more interesting question, to me, was how the debt would be restructured. While not quite as extreme as the 2061 gilts, Thames has a number of long-dated, low cash price bonds in its capital structure and the simplest trade was to buy bonds that were trading below analyst-estimated recovery prices of 70-75c.

The rationale behind that, at it’s core, is based on liquidation economics: where each bondholder is pari-passu and paid the same percentage of par (recovery). But, we know that this will not happen for Thames - the ultimate fallback remains government receivership (SAR). Hence, the resolution of Thames debt will be a restructuring and not a liquidation, dramatically changing the likely outcomes for various bondholders. For example, high coupon bonds are likely to take a haircut on the coupon itself, reducing interest costs. In contrast, low-coupon instruments are more likely to be written down and short-dated instruments to be extended. In general, the overall NPV4 loss is likely to be much more equitable across all of the (class A) bondholders than a simple cash waterfall would imply. Despite this, cash prices are still clustered around analyst estimates for recovery post-restructuring.

Source: LSE

Critically, given that none of this was going be resolved quickly, the March 2025s looked to me as if they were likely to be repaid (and they were). There were also some really interesting trades to be done in the index-linked bonds, for anyone willing to do the heavy lifting on corporate linkers (post RPI reform).

Don’t panic

By the end of 2024 Thames had been junked, shattering the illusion that the Ofwat would ensure IG ratings for the water sector. Public trust in the regulator was rock bottom, amidst a constant stream of scandals over sewerage discharges and evidence that some water companies had been actively misleading the regulator. Successive governments, first the Conservatives and then Labour, were unwilling to foot the bill on rescuing Thames, or to go for an even-more-aggressive debt write down of senior bondholders as contagion across the sector intensified.

Politically there was only one option: blame Ofwat.

A new regulatory regime was clearly required, that would give cover for swingeing water bill increases. As it happens, my late mother was a career civil servant: first in the Ministry of Agriculture; then later MAFF; and then, after the BSE crisis, at DEFRA. Having lived through a departmental crisis once before, I was of the view that Ofwat’s days were numbered (and that, like my mother, most of those involved would succeed to the new regulator).

Souce: Nature.

Ofwat tried to head-off this outcome by unexpectedly giving water companies much more of what they asked for in its December 2024 Final Determination, but it was too late. With the Cunliffe enquiry already underway, Ofwat’s days were numbered. In Q4 I was actively arguing for this outcome, as part of a “the worst is behind us” thesis for the sector.

Specifically for Thames, it appears that everyone has agreed that there is no reason to inject equity without bondholders taking a stiff write down. And bondholders have concluded that if they are going to take a write down, they might as well own the upside of holding the new equity. The transition of debt from bond investors to restructuring and recovery specialists in 2024 has facilitated this immensely.

The remaining sticking point appears to be fines. There is little reason to put equity into a company if the regulator will immediately extract it via fines. But the UK government is still beholden to the court of public opinion, and will struggle to let Thames Water walk away from past offences scot-free.

Given that Thames’ Final Determination has been referred to the CMA (and twice delayed), I will hazard a guess that the most likely way forward is that the CMA will further increase bills for Thames customers, which would allow the new holders of Thames to absorb potential future fines without taking a larger upfront haircut. This would be a win for the current government, as it would push yet more of the blame onto Ofwat while also allowing them to avoid footing the bill for cleaning up the mess. Both literally and figuratively.

There will, doubtless, be more protests in the court of public opinion, but the corpse of Ofwat will provide a convenient scapegoat for Ministers past, present, and future.

Special Administration Process: nationalisation of the water company, in which shareholders are wiped out and the government takes on ownership as a ‘going concern’.

The regulatory perspective was that some of the requested spend was either of spurious benefit to customers or over-costed and could be done at a lower cost to billpayers.

Although in the case of Thames this still has not happened.

Net present value. The current price of the instrument as opposed to its notional value.

Hi Zoso, thank you for the very insightful piece. My question pertains to the dynamics of restructuring if Thames falls into receivership:

"But, we know that this will not happen for Thames - the ultimate fallback remains government receivership (SAR). Hence, the resolution of Thames debt will be a restructuring and not a liquidation, dramatically changing the likely outcomes for various bondholders."

Does the govt have the leeway to decide recovery across board or this will be determined by some committee (including the govt and bondholders)? Moreover, curious as to what happens to the class B creditors in this case.