Bills, bills everywhere!

But let's all stop and think.

On reflection, maybe January was not the optimal time to experiment with a shift to bi-weekly articles. Two weeks into the new year, the US has de-facto made Venezuela a vassal state and seized multiple oil tankers in international waters, while renewing its demands that Denmark cede Greenland. At the same time, there are violent protests in Iran, the White House has ordered Fannie and Freddie to buy $200bn of Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS), the President called for a 10% cap on credit card interest rates, and the DoJ subpoenaed Jerome Powell. Likewise, the President has said that US defence companies will be barred from paying dividends or undertaking stock buybacks, and their CEO’s pay will be capped.

Any one of these would have been a big story for markets also digesting the credit market seasonals of heavy issuance and US mega bank earnings. With many possible topics, I have decided to follow my instincts and write about the thing that annoyed me the most - namely some absolute nonsense on LinkedIn regarding the UK’s Debt Management Office (DMO) floating the idea of allowing savers to buy T-bills.

So, in this article I look at the UK’s T-bill market, why the government wants to issue more T-bills, and how that might affect you and the UK banking system as a whole. For anyone lucky enough to have some spare cash, owning some T-bills could make sense - provided you don’t mind the administrative burden.

Views expressed in this article are my personal opinions and do not reflect the opinions of any institution that I may be associated with. Nothing written in this article should be construed as investment or tax advice.

Mo’ funding, mo’ bills

The UK’s DMO has announced a consultation on the UK Treasury bill market, with the aim of growing the size of the T-bill market both overall and as a proportion of UK government debt. The UK has long been known as an outlier for the long average tenor of the gilt market, but less well known (outside of market participants) is the extremely small size of the UK’s T-bill market.

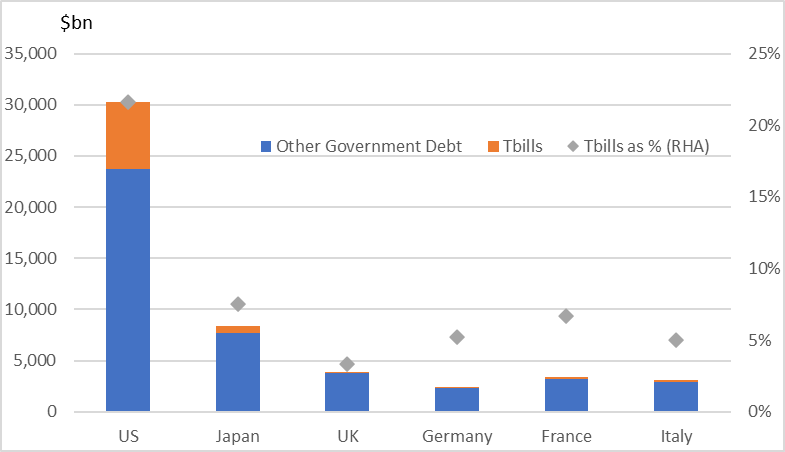

The UK T-bill market is currently just £105bn, versus a total stock of government debt of £2.9trn - or about 3.6% of government debt. This compares to c. 22% in the US.

An ex-colleague of mine has long called for the UK to lean into demand from banks and “Official Investors” by issuing more short-dated gilts and T-bills. But it appears that what has got the DMO to shift is the rapid decline of demand for long-dated gilts from defined benefit schemes - partly because they are closed, so the overall length of their liabilities is shortening, and partly because they are better funded and better hedged in the current interest rate environment. While this trend is acute in the UK, there is a global component here, as demand for long-dated government debt is falling in Japan and the Netherlands for similar reasons1.

Indeed, it’s increasingly clear that the US was ahead of the curve when it shifted its debt issuance to shorter tenors, including T-bills, in 2024. For the US, the motivations were cynical - namely a reluctance to lock in coupons that were, and still are, viewed as “too high” by successive administrations2. But debt management offices around the globe are following suit, as demand for long-term debt falls.

Keeping issuance at the short end allows for a lower cost of funding when the curve is upwards sloping (as it is currently) - particularly if you have reason to believe that interest rates will fall and you will be able to refinance at a lower rate in the future. The counterpoint to this strategy is increased refinancing risk, but the US benefits from exorbitant privilege (and Fed T-bill purchases).

A shift in UK issuance to be more T-bill heavy would be a step towards international norms and is likely to be positively received. But the bit that caused an undue amount of excitement on LinkedIn was the suggestion that direct ownership of T-bills could be opened up to (or even encouraged for) households - in particular Questions 6, 7, 8 of the consultation asking how the government could incentivise or promote retail investment in T-bills and what risks might arise.

Keep calm and issue bills

The idea of UK households holding T-bills directly has prompted some over-excited commentary about monetary policy and banks reserves. Namely, that allowing households to put their savings in government T-bills will rewire the banking system and change monetary policy transmission. Let’s look at the evidence.

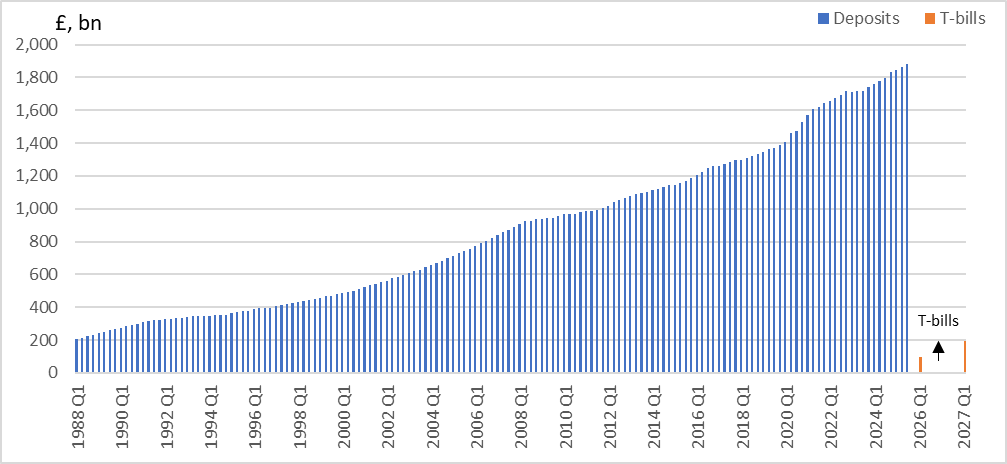

The UK banking system has c. £1.7trn of bank deposits, across both time and sight deposits. So, if the size of the T-bill market doubled, increasing by c. £100bn, and all of that went to households (unlikely) that would only amount to c. 7% of deposits - for context, total household deposits grew by £70bn last year so this would knock back the deposit growth in the short term, but it would hardly be a seismic shift in the composition of bank liabilities.

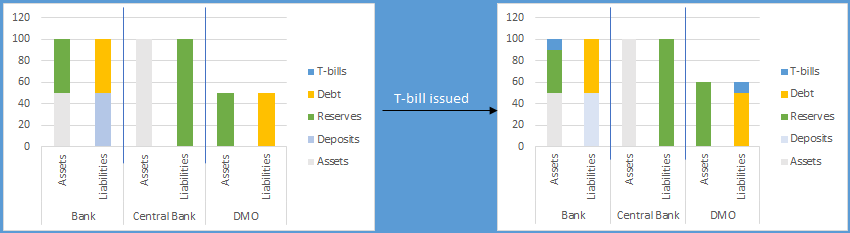

Further, this would all happen on the liability side of bank balance sheets. But, as those of you who have read my primer may recall, central bank reserves are a bank asset. In fact, the impact of households owning government bills on bank reserves would be zero, for two reasons.

First, the DMO question is not about issuing more debt, per se - it is about issuing more bills. Shifting the issuance from gilts (which can already be held by households), to bills shouldn’t be expected to have any effect on the banking system. Or put another way, if households buying bills will have a massive impact on the UK banking system we should have felt this given the popularity of the 2061s.

Second, if we instead assume that T-bill expansion is part of a broader increase in debt issuance, then it doesn’t matter who the buyer of gilts/T-bills is - banking reserves are drained at issuance. This point is subtle, a function of the fact that the government treasury keeps its “cash” in an account at the central bank, as reserves. When the DMO issues debt, reserves are moved from the banking system to the treasury account regardless of who buys the debt. This is why the US Treasury’s General Account (TGA) has become a key part of US money markets - because the US treasury’s “cash” directly impacts the amount of reserves in the system as its balance rises and falls. But this has nothing to do with retail participation.

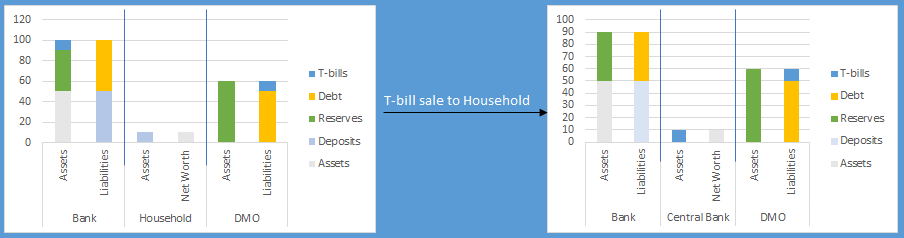

This becomes even clearer if we assume, quite reasonably, that households will not be involved in primary issuance but instead will buy T-bills in the secondary market. In this case the reserves are destroyed at issuance when a GEMM buys the newly issued bills. But when that GEMM sells its T-bills to a retail investor, it’s just a normal exchange of assets, deposits, and reserves

Reports of disruption are greatly exaggerated

The UK selling T-bills to households makes sense, particularly if the government is looking to ramp up issuance in this part of the curve. And as a retail investor I can see some benefit to having access to a source of short-term yield - but it is hardly a free lunch. Buying T-bills means money out of a bank account onto a broker platform, which means it won’t be available for day-to-day use.

And, while T-bill yields will be “guaranteed” if held to maturity, I imagine there will be a relatively large bid-offer, meaning that money withdrawn within 1-3 months will be subject to a “penalty”. That, in turn, means that T-bills are not a replacement for sight-deposits. Instead, they would compete with savings accounts and term deposits - which also compresses the yield pickup materially. For example, the Barclays Rewards Saver account pays 2.10% on months where you don’t make withdrawals, while a 3month T-bill yields around 3.8%: a difference of about £14/month on a £10,000 deposit. Not insignificant, but probably not far above the convenience yield of having your cash available on demand.

Indeed, there are better savings rates out there: Chase are offering BBR+75bp for 12 months (c. 4.5%) to new customers and there are many similar deals. If you are willing to go through the hassle of setting up a broker’s account you could also shop around the various bank savings rates currently on offer.

So, retail T-Bills might generate some interest for UK households who can no longer stuff all their savings into a cash ISA, but the interest rate pick-up versus opening a high interest savings account is negligible and there is a similar level of friction with regard to setting up a new account or accessing the money - and if you are investing for the long term you should be invested in markets anyway.

Much like the growing chorus around stable-coins, most of the commentary on this topic is low-information and readily dismissed when we think about the banking system from first principles.

In the case of the Netherlands, the transition of Dutch pension funds from defined benefits to collective defined contributions is well flagged legal change and has caused a huge amount of speculative trading in long-dated interest-rate swaps.

In playground parlance, Yellen started it.